In this post I'm going to talk about the crucial importance of sound and of listening vs information and using ones eyes when learning to play the guitar.

This may sound utterly redundant and akin to discussing the importance of looking when painting a picture, but I constantly come across students who put more stock in information than they do in sound (or listening).

What I'm talking about here are students who've misinterpreted or been given some bad info either online, or by a friend who is a 'better' guitarist, and who pledge blind allegiance to this information without ever checking what it sounds like.

I've had this happen with 4 students this week alone and it's only Wednesday. In each instance the student swore that I was wrong and that they were right.

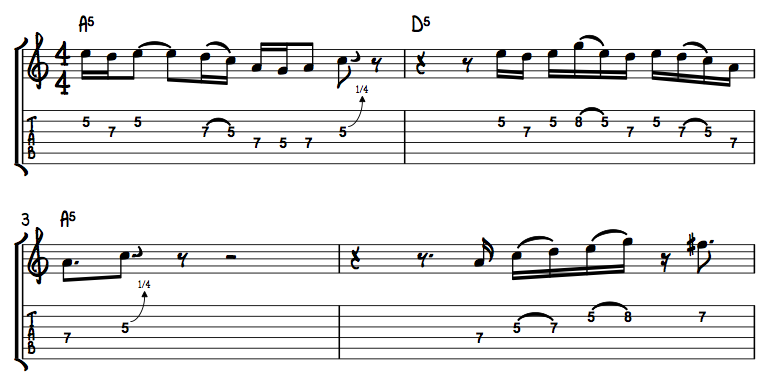

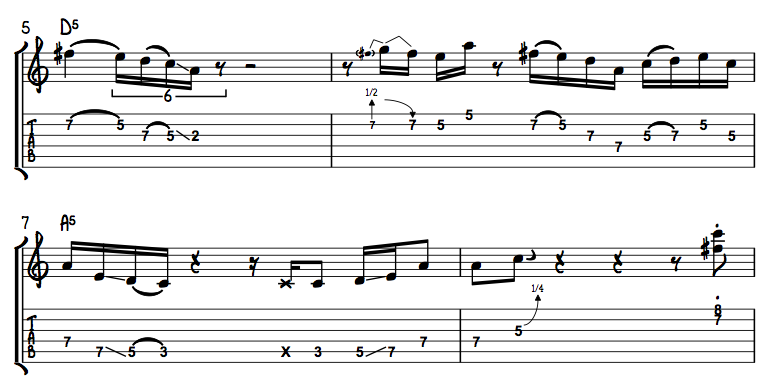

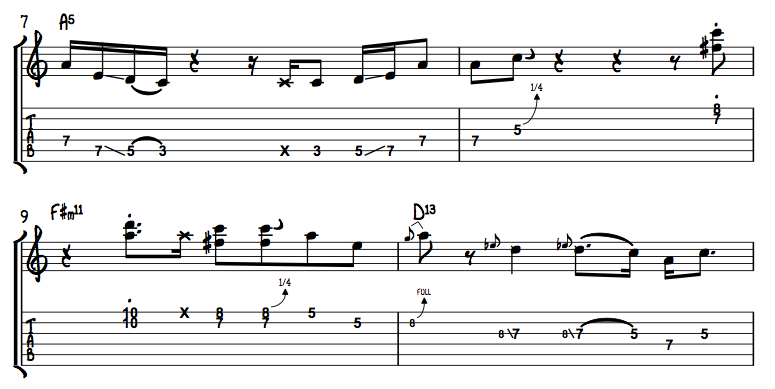

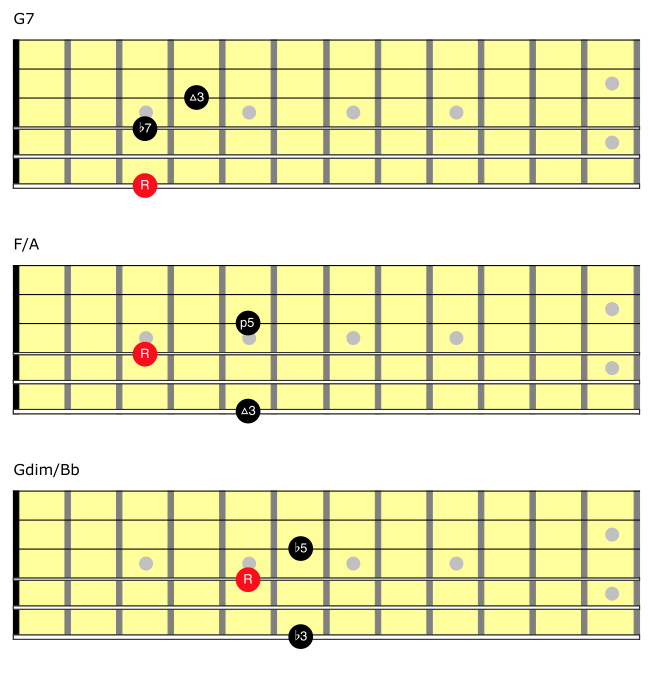

Let me give an example. On Monday a student played an A on the G string (fret 2) instead of an E on the D string (fret 2) misinterpreting what was written in the guitar TAB. The note in question was being played over an E major chord and as such the note E would sound perfectly consonant had it been played. The student was playing the A note however which is a terrible note to play over an E chord and as a result it sounded awful. When I stopped him mid song and told him that he was playing the wrong note he looked at me as if I was mad, told me that he wasn't and pointed triumphantly at the written music in an attempt to prove it. When I illustrated that in fact the note that he was pointing at (in an attempt to prove that he was playing the correct note) was actually on a different string to the one that he was playing he replied 'Well I got half of it right'. He'd got none of it right. He was making a terrible sound, but because it said '2' and he played '2' that was good enough for him.

Now in and of itself a student getting a note or a chord wrong is no big deal but this is illustrative of a fundamentally poor approach to music. In music sound is the currency in which we're dealing yet these students and this approach to music is using only our eyes. This is a phenomenon that I hear about regularly from all of my musician friends who teach and one that I've encountered time and time again myself.

Scott Henderson, the great guitarist and educator once said that 'students are far too concerned with whats happening on here (the neck) and very rarely concerned with what's happening over there (the amp)'. What he meant is that students are using their eyes to determine what to play and not listening to the sound that they are making.

Let's consider that for a minute. It's mental isn't it? It's like listening to our food to decide if we like it or smelling our clothes to decide what to wear.

Now it's fine for you to get your information regarding where/how to play the songs that you're learning from books, from videos, from friends etc (it would be better to work it out yourself but this isn't always possible). What you absolutely must not do however is take this information as gospel without using your ears to verify it. Think of yourself as a musical journalist in this instance, not one of those turds from NME who's more concerned with haircuts and trousers than with music, but in that you must use reliable sources and confirm the sonic information that you're about to use.

We absolutely must, as musicians, learn to use our ears to determine whether what we are playing sounds good. Sure you can look at your favourite players play as a means to try and copy their technique or to establish where on the neck they might be playing a phrase to get a commensurate tone but your ears must be the judge.

This can be hard for people with bad ears. If this is you then you need to do more critical analysis of your playing and more work on your ears.

Use a programme such as transcribe - www.seventhstring.com to help isolate and slow down problematic areas of a song you are learning.

Use something like EarMaster to help bring your ears up to scratch - www.earmaster.com.

Record yourself playing and listen back to it analytically. Do you sound like the song you are trying to play? Are you in time? Do you have the appropriate feel for the song in question? Are you swinging when you shouldn't be or vice versa? Do any of your chords sound suspicious?

Trust me, if you don't use your ears and you only use your eyes then you will never be a good musician. If you don't believe me seek out interviews by luminary guitarists and listen to how they all talk about how they learned to play by listening and copying their influences.

Leave any comments in the comments section and I will get back to you.

James